Now He's "A King"

It is late afternoon on a holiday weekend, and John Smith reminisces while sitting in the shade of his big white house on Dunsmuir's Blackberry Hill.

As he talks, hordes of relatives, mostly young, stop by to give him a hello or a hug. They are on their way to a wedding reception at the community building downtown.

Smith Sanitation owner left Louisiana in 1948 so he could vote.

Smith, who owns Smith Sanitation Service, is not inclined to hurry after them.

The party will last late, he says.

"They say I'm a king now," the 75-year-old Smith says with a laugh. "My family treats me like one. They have respect for me and I love it."

But it was not always that way.

"I was born on October 5, 1922 on a cotton farm in Red River parish, Louisiana," Smith says.

"I only went as far as the third grade in school, and when I was 16 I told my mother I was going to town — to Alexandra - to find a job. That was in 1938.

"I said I was going to take care of my mother. I'd had that dream since I was a little kid and I never gave it up."

Smith says he went to live with his aunt in Alexandra, and almost immediately found a job delivering prescriptions for a small drug store.

"Each of us delivery boys had a bicycle and the drug store owner gave us $50 in change," he says. "The other kids used to stop to talk to their friends, but I made my deliveries and came right back. I learned my way around town by asking people."

"You're smart if you don't wait until you kids are 10 or 15 years old to teach them about work"

John Smith

Before long, Smith got a better job in a bigger drug store.

"The owner was a hollerin' man, but goodhearted,- Smith remembers, "and he took a liking to me. I started out making $5.10 a week there and when I left in 1942 I was making $12.50 a week."

Smith worked his way up to better jobs gradually.

"My mother," he says, "always told me that if you fly too high too soon, you can fall and hit the ground so hard it hurts. So you should go up step by step."

In 1940, Smith married an Alexandra girl, Willie Bell, and in 1942 he was drafted into the army.

After basic training and engineer's school, Smith was granted a leave. But he had a problem.

"My mother said I should always keep enough money in my pocket to get home," he says, "but I'd lost all my train fare gambling on a pinball machine in the post exchange. Then I realized that the PX was selling candy in big boxes. I bought ten boxes and sold the candy bars I'd bought for five cents each to new recruits for 20 cents each. I must have made about $30 or $40, and I took the next train home."

Smith was finally shipped overseas as a member of an ammunition supply company. He was first assigned to Scotland, and on his first night there, "the Germans worked us over pretty good," he said.

About a month after the Normandy invasion, Smith's company was sent to France. From there, he and his fellow-soldiers supplied ammunition to front line troops until the Americans reached Munich.

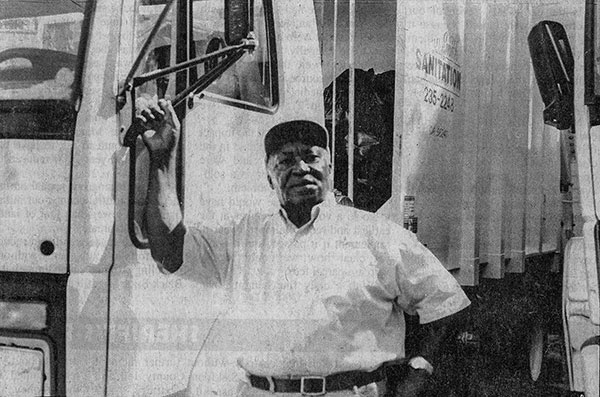

Photo by David Manley

John Smith of Smith Sanitation stands next to one of his two new trucks. His original garbage truck still runs.

It was in the army that Smith began to be concerned with his rights as a black man and as a citizen.

They told us in basic training that Hitler had killed all the blacks in Germany," he says. This was supposed to make us more patriotic. But when I reached Germany I found out it wasn't true. I never believed everything the government told me after that."

Then, one day while he was guarding POWs, a German prisoner told Smith that after the war he was going to move to the United States.

"When I get there," the prisoner said to Smith, "I'll be a white man, and even though you were a soldier, I'll be able to hang you if I want to."

When Smith did get out of the army, he went back to Louisiana where they were paying 50 cents an hour for labor.

"I loved Louisiana and might have stayed even with the low wages," he says, "but by now I wanted to vote. The one thing that made me leave was that they wouldn't let colored people vote."

But for a black man and his family, getting out of Louisiana in 1948 was easier said than done.

"The person at the ticket counter told me, "we don't sell niggers tickets to California," says Smith. "So I had to get a ticket to El Paso, and from there to California."

Smith says he arrived in Fresno, where another aunt of his lived, when he heard someone on the street shouting that he needed workers in his cotton field.

"I gave up the idea of ever becoming a farmer myself when I was in Fresno," Smith said. "You have to worry too much about irrigation in California — in Louisiana we just used God's irrigation."

When he inquired about a job with the Southern Pacific Railroad, a foreman told Smith there weren't any, but that the company was hiring in Dunsmuir.

"Up there in the mountains, the man said," Smith recalls.

So he moved to Dunsmuir and started work right away. His wife and young child followed soon after.

His first day on the Southern Pacific job, Smith says he was told to clean out a pit full of diesel oil.

"I went down there with my soldier clothes and my shined shoes on," Smith said, "and when I got out of there and climbed the hill to my flat I was soaked with diesel oil. The next day when I finished the job, that pit was so clean you could have eaten off it.-

When he arrived home on the second day he burned his clothes.

From 1948 until 1968, Smith worked as a laborer on the graveyard shift.

He held down other jobs, too, because he wanted to build a home for his growing family.

For many years he was the janitor at the California Theatre in Dunsmuir, and he washed walls in people's houses.

He also sent money to his mother in Louisiana until she died in 1951.

Soon, Smith started accompanying a trash collector on his rounds because the collector's clients gave him such wonderful treats.

"I told my wife that when I finished this house, she wouldn't have to move in anything but her clothes."

John Smith

In the early 1950s, the trash collector said he planned to leave the job and asked if Smith wanted to replace him.

So Smith bought a pickup and added trash collecting to his other jobs.

In the meantime, with help from his friends, he built his first home on what was then called Blackberry Hill.

"This whole hill was covered with woods in those days," Smith says. "I used to walk up here with my dog and sit and daydream about a home."

Friends at Southern Pacific installed the wiring and the windows for the home.

Smith said he started to abandon trash collecting several times, but that his customers were so good to him he just couldn't do it.

They even recruited enough new customers so that Smith was able to buy a new pickup.

Step by step, as his mother had taught him, Smith purchased new equipment. First it was another pickup, then a 1958 Ford truck.

By now he had licenses to haul garbage in both Siskiyou and Shasta counties.

On his fourth try, in 1970, his bid to pick up trash in the city of Mount Shasta was accepted, and he finally retired from his other jobs.

John Smith Sanitation now covers territory from the Shasta County line to the Weed Airport. He has been on the job for 27 years and has never missed a day's work.

Actually three of his sons are now responsible for the day-to-day operation of the company.

Charles is the business manager, and William and Jerry work on the trucks.

John and Willie Smith have 12 children: 10 boys and two girls, many of whom went to college with the money their parents saved for that purpose.

"When my kids were about five years old, I began taking them along on my route," Smith said. "I started them out picking up things like Coke bottles and taught them how to work. You're smart if you don't wait until your kids are 10 or 15 years old to teach them about work.The older my kids got, the more work I gave them to do."

His children surround Smith now on Blackberry Hill. Smith himself has built four homes there, and his family resides in most of them.

"We're a big family and we're close," he says. "I raised my kids to be close and they raised their kids to be that way. 'You may fight with others, but never among yourselves,' I've told them."

Smith gestures to the beautiful home behind him.

"I told my wife that when I finished this house, she wouldn't have to move in anything but her clothes," he says. "And that was what she did."

As for Smith's burning desire to be able to vote, he says most of the workers at Southern Pacific were Democrats but "there was one Republican who could sign you up to vote. My Grandfather had talked to me about Abraham Lincoln and how he freed the slaves. I know that most people say the Republican party is the rich man's party, but I liked it because Lincoln freed us and I was on his side."

The hour grows late and Smith grows pensive.

"I didn't just suddenly start wanting something," he says. "It grew in me from a kid. I've worked hard all my life, and now I like to spend a day fishing in Lake Shastina. I love to go out in my boat, cross my legs, and have a couple of beers. I don't even care if the fish bite. I love that. It's my peace of mind."